Note: This guide only works for sites built using Jekyll, including but not limited to GitHub Pages. Feel free to read through the guide to understand the idea behind the approach, but you may need to adapt the code to work with other templating languages.

Introduction#

Markdown syntax is very lightweight and almost resembles normal text, which makes it a very useful tool for writing notes, documentation, and the like. However, because of this simplicity, it lacks some features that are present in more complex markup languages like HTML. One of these features is the ability to create lists and other multiline elements inside table cells.

As a quick refresher, normally, to create a table in Markdown, you would write something like the following:

| Header 1 | Header 2 |

|----------|----------|

| Cell 1 | Cell 2 |

| Cell 3 | Cell 4 |

This will turn into a table like this:

| Header 1 | Header 2 |

|---|---|

| Cell 1 | Cell 2 |

| Cell 3 | Cell 4 |

GitHub Pages and Jekyll#

GitHub Pages provides an easy way for you to write and publish your own website. It is powered by Jekyll, and there are numerous themes and guides available online on how to get started.

In short, Jekyll uses the Liquid templating engine under the hood, which has many features, like using curly braces {{ }} to output variables, {% %} to run code, and more.

We will utilize these features step-by-step to make it easier to add lists and other elements into our Markdown table.

Let’s Create a List Inside a Table Cell!#

The idea is to create a standard Markdown table first. This means using a random placeholder value wherever we need to insert a multiline element. We will then create the table, before using Liquid to substitute this placeholder with the actual content we want to display.

Sidenote: I will be using and interchanging the terms “Jekyll” and “Liquid” quite loosely in this guide, as the details of their distinction are not relevant for what we are going to do. For a better understanding of their differences, feel free to look at their respective documentation: Shopify; Jekyll.

Step 1: Create the Table Layout#

We can use Liquid to create a variable that will hold our “table of placeholders”. Just write the table as you normally would in Markdown, the only difference being, that we surround the table with a capture tag.

{% capture TABLE %}

| Look Below! |

|---------------|

| :placeholder: |

{% endcapture %}

The relevant parts are below:

-

{% capture TABLE %}This is Liquid’s way of creating a new variable. In this case, we call it

TABLE, but it can be anything you want. If you have multiple tables in the same page, you may want to name themTABLE1,TABLE2, …. -

:placeholder:This is the placeholder text that we will replace later. The colons are not necessary; they are just there to make it easy to differentiate a placeholder value. You can use any text you want (e.g.

hello,^123!, etc.), as long as it doesn’t conflict with any other text in your table. -

{% endcapture %}This is the end of the

captureblock. Anything between thecaptureandendcapturetags will be stored in theTABLEvariable. Don’t forget to include it, or Liquid will include everything up to the end of the file!

Step 2: Writing the Actual Data#

This one is quite simple, we will use the same method we did earlier: write out the data as per normal Markdown, but surrounding it with a capture block.

In this case, we will store our data into a variable called TEXT.

{% capture TEXT %}

Here is a list of 2 items:

* Item 1

* Item 2

Now, time for a numbered list:

1. First item

2. Second item

{% endcapture %}

Step 3: Let Liquid Do Its Magic#

Normally, when you are writing Markdown, frameworks like Jekyll will automatically convert the underlying text into HTML, which is what is displayed in the browser.

However, in this case, since we just told Liquid to store whatever we wrote as a variable instead of displaying it, we have to manually take care of the conversion.

Jekyll provides a very useful filter called markdownify, which render the Markdown text into HTML. To view what would have been displayed if we didn’t use the capture block for our list earlier, we can simply do the following:

{{ TEXT | markdownify }}

Note the use of double curly braces {{ }} instead of the curly-percentage {% %}.

Alternatively, to store the converted text into a new variable CONVERTED_TEXT, we can do the following:

{% assign CONVERTED_TEXT = TEXT | markdownify %}

Step 4: Putting it All Together#

Of course, this is not what we want. We want to first:

- Render the table

- Render the text

- Replace the placeholder with the actual text content

Why render first before replacing?

Recall our table:

| Look Below! |

|---------------|

| :placeholder: |

And our text:

Here is a list of 2 items:

* Item 1

* Item 2

Now, time for a numbered list:

1. First item

2. Second item

If we replace the placeholder with our content first, then the resulting value would become:

| Look Below! |

|---------------|

| Here is a list of 2 items:

* Item 1

* Item 2

Now, time for a numbered list:

1. First item

2. Second item |

Which is no longer a valid Markdown table, thus it will not be rendered correctly.

Luckily, there’s also a filter called replace that will, as its name suggests, replace a piece of text with another one of our choosing.

With this, we can now complete our table:

<!-- Step 1 -->

{% capture TABLE %}

| Look Below! |

|---------------|

| :placeholder: |

{% endcapture %}

<!-- Step 2 -->

{% capture TEXT %}

* Item 1

* Item 2

{% endcapture %}

<!-- Step 3 -->

{% assign CONVERTED_TEXT = TEXT | markdownify %}

<!-- Step 4 -->

{{ TABLE

| markdownify

| replace: ":placeholder:", CONVERTED_TEXT

}}

Here, I’ve combined the following steps:

{% assign CONVERTED_TABLE = TABLE | markdownify %}

{{ CONVERTED_TABLE | replace: ":placeholder:", CONVERTED_TEXT }}

Into one statement:

{{ TABLE | markdownify | replace: ":placeholder:", CONVERTED_TEXT }}

By chaining filters together, we can make our code more concise and easier to read.

The Result#

| Look Below! |

|---|

|

Here is a list of 2 items:

Now, time for a numbered list:

|

By combining this idea with Liquid’s other features, we can create truly advanced tables, while focusing on the written content only, without having to worry about styling, layouts, or formatting.

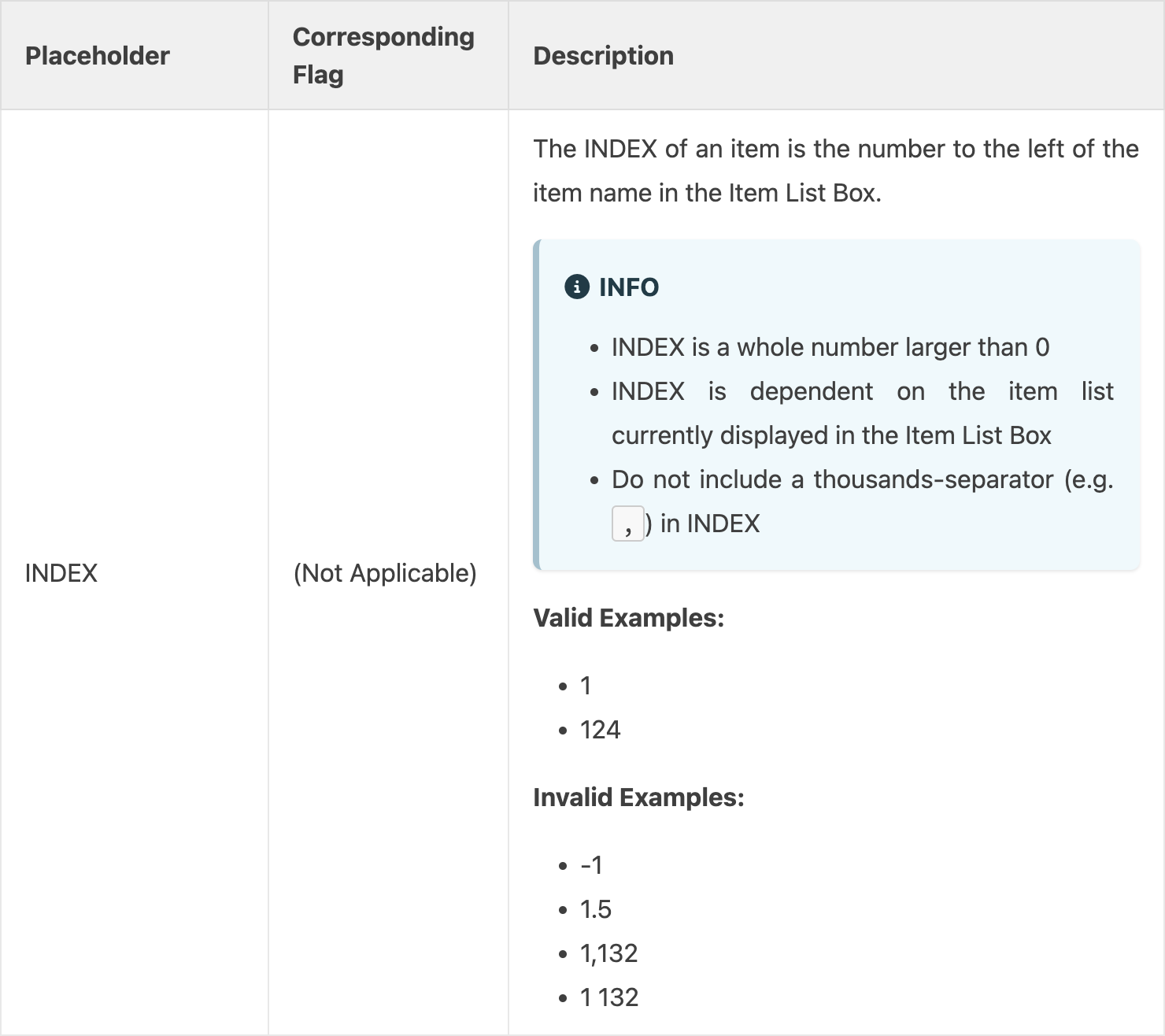

For an example of a practical application for this, you can check out this page, which is a product documentation website created as part of a school project. The following is what one of the rows of the table looks like (do check out the link above for the full table):

Using Jekyll’s include feature, I was able to separate the content for each row of the table into separate files, making it easier for individual team members to update, without having to worry about breaking the table layout.

The full Markdown layout for the table above:

Click here to view the code on GitHub

<!-- ===== DECLARE VARIABLES ===== -->

{% capture INDEX %}{% include_relative _ug/placeholders/INDEX.md %}{% endcapture %}

{% capture ITEM_NAME %}{% include_relative _ug/placeholders/ITEM_NAME.md %}{% endcapture %}

{% capture TAG_NAME %}{% include_relative _ug/placeholders/TAG_NAME.md %}{% endcapture %}

{% capture QUANTITY %}{% include_relative _ug/placeholders/QUANTITY.md %}{% endcapture %}

{% capture UNIT %}{% include_relative _ug/placeholders/UNIT.md %}{% endcapture %}

{% capture BOUGHT_DATE %}{% include_relative _ug/placeholders/BOUGHT_DATE.md %}{% endcapture %}

{% capture EXPIRY_DATE %}{% include_relative _ug/placeholders/EXPIRY_DATE.md %}{% endcapture %}

{% capture PRICE %}{% include_relative _ug/placeholders/PRICE.md %}{% endcapture %}

{% capture REMARKS %}{% include_relative _ug/placeholders/REMARKS.md %}{% endcapture %}

{% capture COMMAND_WORD %}{% include_relative _ug/placeholders/COMMAND_WORD.md %}{% endcapture %}

{% capture KEYWORD %}{% include_relative _ug/placeholders/KEYWORD.md %}{% endcapture %}

{% assign INDEX = INDEX | markdownify %}

{% assign ITEM_NAME = ITEM_NAME | markdownify %}

{% assign TAG_NAME = TAG_NAME | markdownify %}

{% assign QUANTITY = QUANTITY | markdownify %}

{% assign UNIT = UNIT | markdownify %}

{% assign BOUGHT_DATE = BOUGHT_DATE | markdownify %}

{% assign EXPIRY_DATE = EXPIRY_DATE | markdownify %}

{% assign PRICE = PRICE | markdownify %}

{% assign REMARKS = REMARKS | markdownify %}

{% assign COMMAND_WORD = COMMAND_WORD | markdownify %}

{% assign KEYWORD = KEYWORD | markdownify %}

<!-- ===== CREATE TABLE FORMATTING IN NORMAL+ MARKDOWN ===== -->

<!-- WE USE :variable: FOR VALUES THAT ARE TO BE SUBSTITUTED -->

{% capture TABLE %}

| Placeholder | Corresponding Flag | Description |

|--------------|---------------------|----------------|

| INDEX | (Not Applicable) | :INDEX: |

| ITEM_NAME | n/ | :ITEM_NAME: |

| TAG_NAME | n/ | :TAG_NAME: |

| QUANTITY | qty/ | :QUANTITY: |

| UNIT | u/ | :UNIT: |

| BOUGHT_DATE | bgt/ | :BOUGHT_DATE: |

| EXPIRY_DATE | exp/ | :EXPIRY_DATE: |

| PRICE | p/ | :PRICE: |

| REMARKS | r/ | :REMARKS: |

| COMMAND_WORD | (Not Applicable) | :COMMAND_WORD: |

| KEYWORD | (Not Applicable) | :KEYWORD: |

{% endcapture %}

<!-- ===== RENDER THE ACTUAL TABLE ===== -->

{{ TABLE

| markdownify

| replace: ":INDEX:", INDEX

| replace: ":ITEM_NAME:", ITEM_NAME

| replace: ":TAG_NAME:", TAG_NAME

| replace: ":QUANTITY:", QUANTITY

| replace: ":UNIT:", UNIT

| replace: ":BOUGHT_DATE:", BOUGHT_DATE

| replace: ":EXPIRY_DATE:", EXPIRY_DATE

| replace: ":PRICE:", PRICE

| replace: ":REMARKS:", REMARKS

| replace: ":COMMAND_WORD:", COMMAND_WORD

| replace: ":KEYWORD:", KEYWORD

}}

This also makes it really easy to reorder the rows as needed, and gives everyone a rough idea on what the final table will look like from a quick glance, without having to actually render the table.

Conclusion#

Why is this useful? Well, for one, it allows you to create more complex tables that contain lists, code snippets, or even images. This can be very useful for documentation, tutorials, or any other content that requires a more structured layout.

Secondly, it allows you to separate content from layout. This means that you can have one person focus on writing the content, while another person can focus on styling the content. This can be very useful in a team setting, where different people have different roles, and where some people may not be familiar with Markdown or HTML.

Have you ever had the need to create a table with lists or other multiline elements inside? What was it for? How did you solve it? Let me know by reaching out!

TL;DR: Follow along using the GitHub Gist instead

A summary for this post can be found in this link: gist.github.com/RichD...3d0640.

Stay tuned for more Jekyll tips and tricks!